For most socially challenged kids, high school becomes the final torment — a kind of ninth circle — at the end of an already unpleasant progression of mismatched interactions, rejections and instances of outright abuse. But somehow I really lucked out. For me, high school was the turning point: away from the solitude of childhood; toward a brighter world of adults and the promise of a society of shared thoughts and beliefs.

For most socially challenged kids, high school becomes the final torment — a kind of ninth circle — at the end of an already unpleasant progression of mismatched interactions, rejections and instances of outright abuse. But somehow I really lucked out. For me, high school was the turning point: away from the solitude of childhood; toward a brighter world of adults and the promise of a society of shared thoughts and beliefs.

I remember a crazy and over-dramatic vow I made at about age 15. Lying on my bed, I declared (with tears in my eyes) that one day I’d discover a different sort of life, a life in which I could carve out a safe and comfortable place in the world, even beyond the sanctuary of my bedroom. In that imagined future life, I wouldn’t measure my success simply by how well I passed undetected, managing to keep my head below the radar of my peers. Instead I’d participate actively in a society of people who accepted me — even liked me — for the thoughts and feelings, desires and dislikes I expressed openly. As crazy as it sounds, I stumbled into that new society in a northern Arizona high school, filled with the oddest demographic mix a boy from the east could have imagined.

Amidst the Mormon cheerleaders and football players, the kids of Mexican immigrants, the students bused in from the Navajo and Hopi reservations, I settled into an odd little group of like-minded people.

Drugs were the glue that united the larger expanse of that group, bringing together kids with little else in common beyond the secret practice of procuring and indulging in illegal substances. But at the core of that assembly of stoners and misfits were the people with whom I really bonded. And while drugs may have been the general glue for the larger group, among my friends, they were only one aspect of our shared quest of exploration and discovery.

Drugs were the glue that united the larger expanse of that group, bringing together kids with little else in common beyond the secret practice of procuring and indulging in illegal substances. But at the core of that assembly of stoners and misfits were the people with whom I really bonded. And while drugs may have been the general glue for the larger group, among my friends, they were only one aspect of our shared quest of exploration and discovery.

We were 16. And, for the first time, we began to feel that we had the power to shape the course of our lives as they stretched out ahead of us. And that course still looked untouched, unformed and full of potential, like a field of new snow in which we were about to leave our footprints. The future wasn’t the scary place it sometimes becomes as we grow older. It was a glorious sea of unrealized possibilities. It was all there for us to mold and shape into the perfect images we talked about late into the night.

Don’t get me wrong: drugs were still a big part of our experience. And much of it was pure fun and giggle fests. [Oh, the disturbing beauty of all those cereal boxes in the Safeway when your LSD just starts to kick in. And how long those aisles have become. And what is up with that woman’s hair? Is she real or just a prop put here to freak out the other shoppers?]

But it was also much more than that. We read the books of Carlos Casteneda and tried to recreate his hallucinations during our dusk-to-dawn peyote camp-outs. We read the books of Aldous Huxley and discussed the future of society over the batch of purple microdots that hit town that fall and winter. And every time — all the time — we listened to music. That music wasn’t just the soundtrack playing behind our primary activities; it was intricately woven into everything we did and everything we thought. That music not only changed the way I heard, but it changed the way I thought about the world, about the power of ideas to affect material things and the power of art to affect the culture around it.

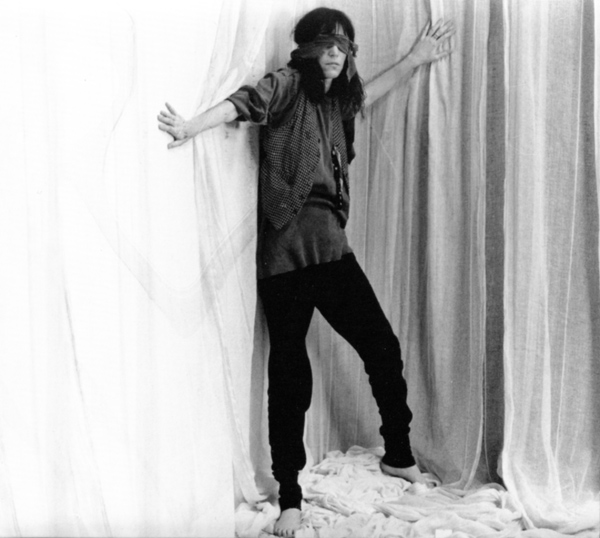

One friend in particular was responsible for bringing the rest of us to the music he’d found. The early solo albums of Brian Eno; the music of David Bowie — particularly the then recently-released albums from Berlin — and Patti Smith. My head would spin with the implications of what they were saying, of the sounds they were creating, and of the way they looked in those gorgeous images on the LP sleeves.

I know this is already sounding corny; but I can’t say enough about how much those albums changed my view of the world and my place in it. And one album in particular became the window through which I could see the transforming effect of spoken words and an electric guitar on the world outside. I spent hours listening to my friend’s precious copy of Horses, lying on the floor of my bedroom with the speakers from my portable stereo pulled close to either side of my head.

Even to start a description of the album as a whole would take a small book. And fortunately, someone’s already done that.

[How cool is this series from Continuum: 33 1/3? Each slim volume is devoted to a single, but seminal album. They get a little academic in their tone. But even to buy such a book, you have to love its subject deeply. And that allows you to forgive a fellow devotee even a bit of pedantry.]

But I can share a specific and most vivid experience in a reasonable amount of space right here.

The second to the last track of Horses is the three-part piece entitled “Land.” Its three sections — distinct but intricately intertwined — are named “Horses,” “Land of a Thousand Dances,” and “la mer (de).”

The first section tells the story of a boy who seems to implode in the hallway of his high school as his own image attacks and humiliates him. With the driving chant “Horses, coming in in all directions,” the track segues into “Land of a Thousand Dances” (Smith’s re-working of the tune probably made most famous by Wilson Pickett): “Do you know how to Pony?” And from there, we return to the story of that boy from the high school hallway … sort of.

This last segment, entitled “la mer (de),” is what one witness in the 33 1/3 book refers to as “the poetry part.” By Smith’s own account, she simply froze on the first attempt to record the vocals for the segment and could only muster a few cryptic lines — “Build it.” “Let it calm down.” — as if she were giving technical direction to the band.

Since the instrumental tracks were to everyone’s liking, Smith went back to the microphone to record her vocals separately. What came out wasn’t the verse she’d reworked over several years’ time. It was, as she described it, “…like it was the Exorcist or somebody else talking through my voice.”

Since the instrumental tracks were to everyone’s liking, Smith went back to the microphone to record her vocals separately. What came out wasn’t the verse she’d reworked over several years’ time. It was, as she described it, “…like it was the Exorcist or somebody else talking through my voice.”

Wherever it came from, everyone liked the track. Smith recorded two more takes and then sat down in a seven-hour session to mix all three, layering and weaving voice over voice to create a dreamy string of blank verse and oblique associations. The result was a form of poetry that simply couldn’t exist outside of a multi-track recording studio.

It’s the business of poetry to build imagery and allusions as the work progresses; such that, as they accrue, meaning and reference seem to spin off in all directions, touching other, disparate parts of the verse.

But in this case, we don’t have simply that linear (horizontal) progression of words into sentences, forming meaning through syntax over time. Instead, the multiple layers of sound and phrases allow these collisions of sense to move up and down — vertically among the various levels or tracks we can hear — as well as horizontally.

The method produces sense and imagery which feel like they’re spinning almost beyond our ability to follow them in any logical way. They urge us to let go; to allow sense and meaning to bang around freely in our heads; to allow fresh, new associations to condense quickly in unexpected places, creating surprising new meanings before they evaporate and we’re on to the next drop of condensation.

Now, that must sound like a precious observation; but give me a chance here. Think of that 16-year-old lying on the floor of his bedroom with a speaker pressed against each ear. Think of the wonder in his mind at the world ahead, of his first taste of the possibilities his life presents for the years to come. And imagine his eyes closed tightly as these various and multiplying connections and associations of meaning and allusion are bounding around in his brain, spinning off of each carefully crafted piece of verse.

I’ve tried to illustrate what’s going on here, to map out the sparks of meaning that fly off of one verse and ignite another with emotion and importance. But somehow that very process of putting it all under a microscope sucks much of the life out of it. It’s as if, to look at it really closely, we end up chloroforming it and sticking it through with a pin.

But listen to it for yourself. After all, the verse only holds the potential for meaning. It’s only when it’s banging around inside the listener’s head that it picks up enough energy to change the way he looks at the world around him.

Well, at least give it a try.

I guess most of us associate particular bits of music with different ideas or memories or seasons. But the music from those last two years of high school don’t belong to a moment in time for me. They embody a whole view of the world that’s often faded over the years as my own sea of possibility and potential hardened into the choices I’ve made — for better or for worse — and I watched the options ahead narrow and diminish, my liquid dreams of the future dry up and solidify.

But I’m happy to report that this view of the world has never left me entirely. I only need to hear the opening line of the first track of Horses and I remember that it’s never too late to shape the world around me through my thoughts, words and deeds. That sea of possibility floods a little bit, even if not to the edge. The solidified dreams of the future begin to loosen and slip. And even if it only means banging out a single sorry installment of this blog each week, I believe I can still affect my little corner of the universe.

Jesus died for somebody’s sins, but not mine.